What Is Promoting Action On Research Implementation In Health Services (Parihs) Framework

- Debate

- Open Access

- Published:

PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice

Implementation Scientific discipline volume xi, Article number:33 (2015) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

The Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Wellness Services, or PARIHS framework, was start published in 1998. Since this time, work has been ongoing to further develop, refine and exam it. Widely used equally an organising or conceptual framework to help both explain and predict why the implementation of evidence into practice is or is not successful, PARIHS was one of the first frameworks to brand explicit the multi-dimensional and complex nature of implementation as well as highlighting the central importance of context. Several critiques of the framework have also pointed out its limitations and suggested areas for improvement.

Discussion

Building on the published critiques and a number of empirical studies, this newspaper introduces a revised version of the framework, chosen the integrated or i-PARIHS framework. The theoretical antecedents of the framework are described likewise as outlining the revised and new elements, notably, the revision of how evidence is described; how the individual and teams are incorporated; and how context is further delineated. Nosotros draw how the framework can be operationalised and draw on case study data to demonstrate the preliminary testing of the face and content validity of the revised framework.

Summary

This paper is presented for deliberation and word inside the implementation science community. Responding to a series of critiques and helpful feedback on the utility of the original PARIHS framework, we seek feedback on the proposed improvements to the framework. We believe that the i-PARIHS framework creates a more integrated approach to understand the theoretical complexity from which implementation scientific discipline draws its propositions and working hypotheses; that the new framework is more coherent and comprehensive and at the same fourth dimension maintains information technology intuitive appeal; and that the models of facilitation described enable its more than effective operationalisation.

Groundwork

In 2008, the PARIHS group published a paper in Implementation Scientific discipline that summarised the work over the previous 10 years in developing and refining the PARIHS (Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services) framework [1]. From its inception, PARIHS argued that successful implementation (SI) of bear witness into practice was a role of the quality and type of evidence (E), the characteristics of the setting or context (C) and the manner in which the evidence was introduced or facilitated (F) into practice. Each of these dimensions was further subdivided into a number of sub-elements that needed to exist considered in order for implementation to be successful [two, iii].

The 2008 paper outlined three linked areas of work in developing PARIHS, namely, conceptual evolution [4–six], empirical testing and refinement [7] and the development of reliable measures to diagnose and evaluate an arrangement's readiness for change and the effectiveness of that alter [8–10]. It concluded past identifying a number of challenges including the need for more than theoretical work on the conceptual framework, the need to set more rigorous ways to develop and test the diagnostic and evaluative methodologies and associated instruments based on elements of PARIHS and the need to agree upon the practical contents of a facilitator preparation programme that would equip facilitators to know how to operationalise the framework. After, both PARIHS squad members [11–thirteen] and other research teams [14, 15] have been involved in studies to evaluate and refine the framework further. These studies have reinforced some of the conclusions of the 2008 paper and identified some additional issues for consideration. For example, Helfrich and colleagues [14] undertook a critical synthesis of the literature on PARIHS and identified a number of perceived limitations to its effective utilisation. These included the lack of evidence from prospective implementation studies on its effectiveness; lack of clarity between elements and sub-elements of the framework; a predominant focus on the facilitation role rather than the facilitation process and the lack of a clear definition of what successful implementation really was. Building on this review, a revised PARIHS framework was put forrard, including a detailed diagnostic tool based on the refined elements and sub-elements of the framework [15].

A repeat search in 2014 using the aforementioned databases and search terms as the review by Helfrich and colleagues in 2010 [xiv] identified over 40 more than papers that reported applying PARIHS [sixteen]. This indicates standing involvement in using the framework and reinforces what Helfrich and colleagues observed in terms of the framework's intuitive appeal and relevance to the real globe setting. However, prospective studies remain limited. I exception to this is a prospective study on peri-operative fasting, which used PARIHS to blueprint a businesslike trial to test the effectiveness of the introduction of guidelines to improve do [12, 17]. From their analysis, the authors suggested that an additional weakness in the framework was the failure to acknowledge the central role of individuals in determining the process and outcomes of implementation, mediated through private interactions with and influence on the evidence and context dimensions of PARIHS. Useful findings have likewise emerged from reviews that take compared PARIHS to other implementation frameworks and models. Tabak and colleagues reviewed over 60 models and frameworks and suggested that PARIHS lacked a focus on the system and policy level of implementation [18]. Flottorp and colleagues also undertook a review of frameworks and their findings indicated that PARIHS failed to pay attending to the individual health professional person and the wider social, political and legal context of implementation [nineteen].

Our own ongoing application of the framework in implementation studies (see, for example, [11, 13, twenty–22]) together with critiques and evaluations of the framework past other research teams has led us to create a refined version of PARIHS. It is called the integrated or i-PARIHS framework. This paper describes the revised framework, outlines the new elements and explains why the changes have been made. Inside this discussion, we draw on empirical data from three case studies of implementation (summarised in Tabular array one). The paper then describes how the i-PARIHS framework can exist operationalised and summarises the underpinning theoretical antecedents of the framework. We conclude the newspaper by raising some questions for further consideration and outlining plans for futurity research and development activity.

Main Text

The principal reasons for re-visiting the original PARIHS framework included:

-

The original framework failed to address key dimensions, including the intended targets for implementation and the wider external context (social, political, policy and economical) in which implementation occurs [14, 18, xix]

-

Growing bear witness on the key role individuals play in the implementation procedure [12]

-

Increased involvement and awareness of relevant theories that tin can and should inform implementation strategies [23–25]

-

Recognition of the diverse ways in which people were applying PARIHS, not simply to guide the implementation of more conventional inquiry evidence in the form of clinical guidelines or show summaries, but to inform and evaluate developments in practice more generally [26]

Based on our assay of these issues, we are proposing the revision of the key constructs of show, context and facilitation and suggesting the add-on of a new construct termed 'recipient'. The original PARIHS framework was expressed as a simple equation (Table 2). Critics have rightly pointed out that nosotros did not ascertain what successful implementation meant [14, fifteen]. In our revised, i-PARIHS framework, successful implementation is primarily specified in terms of the achievement of implementation/projection goals and results from the facilitation of an innovation with the recipients in their (local, organisational and wellness system) context (Tabular array 2). The core constructs of the i-PARIHS framework are facilitation, innovation, recipients and context, with facilitation represented as the active element assessing, aligning and integrating the other 3 constructs. As illustrated, a number of other characteristics of successful implementation are proposed, reflecting the multi-dimensional nature of the constructs.

The innovation construct

The original PARIHS construct of show adopted a broad view of evidence, comprising data from research, alongside clinical, patient and local experience [vi]. In i-PARIHS, we have farther extended the construct to embrace a more explicit view of how the characteristics of knowledge impact its migration and uptake in dissimilar settings. This includes the more emergent, inductive ways in which evidence is generated from exercise as, for example, inside practice evolution initiatives in nursing and healthcare [27–29]. Our proposition is that people rarely take evidence in the original form of a systematic review or clinical guideline and directly apply it within an implementation projection rather they incorporate show in a number of different ways, which typically involves adapting the original evidence in some way to suit their particular situation, a procedure described by some as 'tinkering' [30] whereby explicit knowledge is blended with tacit, practice-based cognition.

This is clearly apparent in 1 of the cases nosotros draw on in this paper, namely a project to improve the identification and management of chronic kidney illness (CKD) in a healthcare region in England [21, 31]. Aware of the potential to ameliorate CKD, the team leading the projection accessed a recently produced national clinical guideline on the identification and management of CKD in principal care [32]. However, rather than setting out to 'implement the guideline', a number of prior processes were put in place. Firstly, a local stakeholder group comprising patient representatives, clinicians from acute and primary care, researchers and managers was established to consider the evidence and agree on the priorities at a local level. This involved taking into consideration existing policies and practice at the local level, including the CKD related measures in the national pay-for-operation arrangement in primary intendance and the local rates of achievement on these indicators. From the stakeholder deliberations, a decision was made to distil the evidence from the guideline into two overarching aims related to improving the identification of CKD patients within a practice population and, once identified and on a practise annals, to improve the direction of patient blood pressure to evidence-based targets.

This process of aligning external explicit show with local priorities and practise is an important way of enhancing the compatibility of a proposed modify, equally recognised in the innovation literature [33–35]. For these reasons, we have re-labelled the construct 'innovation', incorporating Rogers' seminal work on the diffusion of innovations [33, 34] and other central studies on the nature of innovation within and exterior healthcare [35, 36]. We argue that evidence is ane type of knowledge and (new) cognition is the substance that needs to be introduced in club to generate modify and improvement. The characteristic of the knowledge creates a set of conditions that make information technology more or less likely to exist recognised and applied. This phenomenon is well described in Roger's Diffusion of Innovations Theory [33, 34], for example, in terms of the probable fit of the new noesis with existing practice, the relative advantage it presents and potential trialability. We are therefore proposing 'innovation' every bit a fundamental construct within the i-PARIHS framework but with an explicit focus on sourcing and applying available research testify to inform the innovation. Table 3 summarises the primary characteristics of the innovation to be considered in implementation.

The recipient construct

This is a new construct, added in response to consequent feedback that bereft attention had been paid in the original framework to the actors involved in implementation. Although reviews and empirical studies applying PARIHS have emphasised the importance of the private on implementation processes and outcomes [12], we are proposing recipients as a construct that encompasses the people who are affected past and influence implementation at both the individual and collective team level. This extension enables the i-PARIHS framework to consider the affect individuals and teams have in supporting or resisting an innovation. We accept elected to consider recipients at both an individual and collective level as alongside research highlighting the importance of individuals in supporting or resisting change [12, 37]; there is good evidence to propose that groups or teams of individuals accept an of import role in determining the uptake of new knowledge in practise. This is particularly evident in studies that have been undertaken on communities of practice and the notion of commonage 'mindlines' influencing the uptake (or non) of evidence in practice [38–40].

The CKD case study illustrates one way in which actors at the local level tin influence the course of implementation, equally 1 of the challenges encountered was whether exercise staff perceived value in 'labelling' patients with CKD. This was particularly the example for older patients as some General Practitioners (GPs) and practice nurses viewed failing renal function as a natural part of ageing and believed that disclosing a diagnosis of CKD could cause unnecessary feet in patients. By adopting this arroyo, opportunities to better self-management and overall management of cardiovascular disease and to address the issue of increased susceptibility to acute kidney injury were potentially missed [41].

A second case report which elucidated the key part of recipients focused on the implementation of evidence-based recommendations for the management of continence in a nursing home setting [42]. Focusing on goals to meliorate the assessment and attainment of continence amongst residents, a key expanse was addressing care staffs' strongly held views equally to whether such goals were achievable, especially where residents had been managed every bit 'incontinent' over prolonged periods of time. This required a meaning amount of effort to change the mindset amongst nursing home staff about achieving continence. Various strategies were helpful in this regard, including input, support and practical guidance from a continence nurse specialist. In ane nursing abode, the staff responsible for facilitating implementation collected stories from residents about their feel of living with incontinence, which provided a very powerful motivational tool to convince their colleagues of the demand to alter.

As these examples illustrate, the people involved in implementation, including their views, beliefs and established ways of practice, tin significantly affect the ease of introducing an innovation or change. A wide range of stakeholders potentially fit into the construct we have labelled 'recipients' including patients and clients, clinical staff and managers. It is likewise apparent that the relationship betwixt the innovation and the recipients is in many ways an inter-dependent i. Given this set of circumstances, part of the facilitator's function at the recipient level involves assessing the actual and potential boundaries that be and the ways in which these barriers might exert an influence during implementation [43]. Table 3 identifies the main characteristics of the recipients at the individual and collective level.

The context construct

Context remains a cadre construct within i-PARIHS just with a wider focus on the dissimilar layers of context, from the micro through the meso and macro levels, that can act to enable or constrain implementation. In the PARIHS framework, we defined context in terms of resources, culture, leadership and orientation to evaluation and learning; however, we did not delineate between the immediate local context and the wider organisational context. Furthermore, we did non explicitly consider the impact that the wider health system—the external context—could have on implementation processes and outcomes. These meso and macro level contextual factors take been recognised as important considerations, for example, in other implementation frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [44] and in reviews of models and theories of implementation [nineteen]. We have also observed their influence in our own empirical research. For example, in the instance report on promoting continence, in some of the countries studied, a focus on continence formed part of the external accreditation system for nursing homes. This created a driver for introducing changes to better the management of continence at a local level [45]. Similarly in the instance study of CKD, the presence of CKD indicators in the pay-for-performance organisation in primary intendance created an incentive for improvement [21].

In a third case study that focused on the prevention and reduction of weight loss among older patients in an acute hospital setting, a number of contextual factors were important, particularly at the organisational level [46]. The implementation projection introduced iii prove-informed interventions, one of which was the provision of oral nutritional supplements for older patients at risk of malnutrition. Nonetheless, the reality of making these supplements bachelor at the point of care delivery required the agreement of financial support to make the supplements, and the fridges to store them in, available in the ward setting. Furthermore, negotiations with the stocks department were needed to address the issue of stock supply and management. These are typical of the sort of organisational context issues that accept to be considered inside the procedure of implementation.

Consequently, in the i-PARIHS framework, we have made a distinction between the layers of inner and outer context, where inner context includes both the firsthand local setting, whether a ward, unit, hospital section or primary intendance team, and the organisation inside which this unit or squad is embedded. Outer context refers to the wider wellness system in which the organisation is based and reflects the policy, social, regulatory and political infrastructures surrounding the local context. Table 3 illustrates the differentiation of inner and outer context at the micro, meso and macro levels.

The facilitation construct

As with the original PARIHS framework, facilitation remains a cadre construct. Still, nosotros emphasise facilitation as the active ingredient within i-PARIHS by positioning information technology differently to the other main constructs of innovation, recipients and (inner and outer) context (Table 2). We advise that facilitation is the construct that activates implementation through assessing and responding to characteristics of the innovation and the recipients (both as individuals and in teams) within their contextual setting. This requires a function (the facilitator) and a set of strategies and actions (the facilitation process) to enable implementation. The i-PARIHS framework therefore locates the success or otherwise of implementation upon the ability of the facilitator and the facilitation procedure to enable recipients within their particular context to adopt and apply the innovation by tailoring their intervention accordingly.

We have adopted this position for a number of reasons, both experientially and empirically based. Tracing the history of facilitation equally a concept in healthcare [5], there is a tradition of applying facilitator roles to back up the implementation of changes in do. From the introduction of facilitators to promote principal care prevention programmes in the 1980s [47], the utilize of facilitators in primary care has become commonplace, particularly supporting the implementation of change through quality comeback methods [48–51]. A 2012 systematic review of practice facilitation in main intendance concluded that practices supported past a facilitator were two.76 times more than probable to adopt evidence-based clinical guidelines [52]. Within the 23 studies reviewed, facilitators employed a number of different facilitation strategies, in detail inspect and feedback (used in 100 per cent of studies) and interactive consensus building and goal setting (91 per cent use), alongside reminders, tailoring to context and quality improvement tools such equally Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles. This concurs with our own experiences of applying facilitation to support the development of standards, audit and quality improvement in nursing and wellness intendance [53, 54]. More recently, the utilise of facilitation has been evaluated in a number of other settings. For instance, the NeoKIP (Neonatal Knowledge into Practice) trial evaluated the effectiveness of facilitation as a cognition translation intervention for improved neonatal health and survival [55]. Using lay members of the community who received training in facilitation techniques such every bit PDSA and group consensus edifice, the study demonstrated a reduced neonatal mortality of 49 % in the 3rd year of the intervention [56]. In the U.s. Veterans Health Administration, a number of studies take demonstrated the benefits of using facilitation to support the implementation of prove into clinical practise (for example [57, 58]), whilst in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, facilitators have been employed to back up the implementation of show-based vascular care [20, 21], as described in the CKD case study.

To fulfil the role effectively, facilitators have to exist able to office in a flexible and responsive manner to tailor their approach to the particular issue, setting and people involved; hence, our proposition that facilitation comprises the agile chemical element of implementation. However, every bit the case studies in Table 1 illustrate, bear witness from effectiveness studies of facilitation is mixed. This probable reflects the fact that facilitation itself is a complex intervention, involving 1 or more individuals in the part of facilitator, applying a combination of improvement and team-focused strategies to enable and support alter. In some cases, facilitators are internal to the implementation setting; in others, they are external and sometimes a combination of internal and external facilitators is used. Studies that written report process evaluation alongside effectiveness data demonstrate the importance of having the correct individuals in the role with the right level of skills, cognition, support and mentoring [59, 60]. This highlights the need to consider bug of facilitator recruitment, selection, preparation and development when designing and conducting implementation studies that utilize facilitation as an intervention. These are issues that we have taken into consideration in our proposed operationalisation of facilitation inside i-PARIHS.

How the i-PARIHS framework is actioned

A consequent criticism of the original PARIHS framework was that it was hard to operationalise [xv]. In developing the i-PARIHS framework, nosotros take used ongoing empirical enquiry from our ain and other teams' awarding, evolution and evaluation of PARIHS to present a practical model of facilitation (meet for case [11, 21, 22, 45, 55, 61]). This has led to the evolution of a preliminary Facilitator's Toolkit utilising quality improvement and audit and feedback methods and too a more structured arroyo to the identification, training and development of facilitators within and across systems [62, 63]. (For a more detailed description of the facilitation model and toolkit, see [63]). Specifically, we are proposing a facilitation pathway from beginner or novice facilitator to experienced and expert facilitator, bold dissimilar roles in the process of implementing and researching the implementation of new knowledge into practice [62].

Positioned as the active ingredient, facilitation is undertaken past 1 or more than trained facilitators, who assist to navigate individuals and teams through the complex change processes involved and the contextual challenges encountered. Facilitators tin can either exist internal to the system, external to information technology or a combination of both, as the 3 case report examples illustrate, with a mix of internal-external and novice-experienced-proficient combinations. This reinforces that there is not a single right style to utilize facilitator roles; even so, there are clear benefits in mechanisms that provide back up and mentoring to new or less experienced facilitators. In case 1, this was achieved through having teams of novice and experienced facilitators working together and by bringing in novice internal facilitators to build local capacity for facilitating implementation. In instance 3, facilitator pairs were formed to part model inter-disciplinary working and provide mutual support, supplemented by support from external, adept facilitators in the co-located university. In all three cases, the methods employed by facilitators typically involved improvement approaches such as Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles and inspect and feedback, underpinned by project management. This helped to address central issues such as establishing clear goals, demonstrating the potential for comeback, providing regular feedback and trialing changes on a modest—all of import factors in terms of securing and maintaining staff motivation and commitment.

The facilitator needs to have a audio agreement of the nature of the innovation being introduced (the focus and content of implementation), the individuals and teams that accept to enact the change (the recipients) and the environment in which they work (the local, organisational and health system context). This essentially involves thinking about what is to be implemented, who with and where. Facilitation provides the how component of implementation.

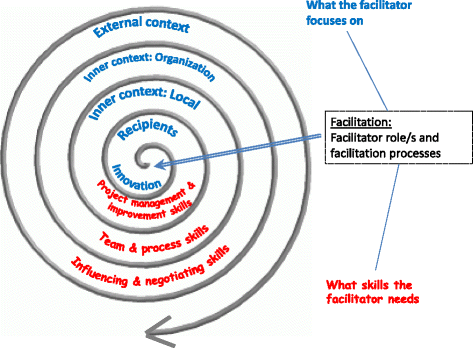

In gild to assist the facilitator sympathise the dynamic nature of implementation, we accept chosen to stand for the i-PARIHS framework equally a continuous spiral which starts with a focus on the innovation and the recipients, moving out to the different layers of context (inner context at local and organisational level and outer context at wider organisation and policy level). Figure 1 summarises what the facilitator looks at within each of these levels and also summarises the sort of activities they need to undertake; in other words, what they accept to exist able to practice. This effectively involves progressing from a focus on the more specific, concrete aspects of implementation to addressing the contextual factors and barriers that are likely to influence the trajectory of the implementation journeying. Our hypothesis is that the further out into the spiral the facilitator moves, the greater the level of feel and skill they will need. This in turn suggests that whilst novice facilitators may be able to support locally focused implementation projects (in terms of working with a local squad to program and undertake the project), they are likely to need the support of a more experienced facilitator to assess and negotiate some of the more than challenging barriers or contextual factors they may encounter.

The facilitation role and process

This leads usa onto another of import consideration near the need for facilitators to work within a supportive network, ideally mentored and supported by peers and more experienced colleagues, as is evident in the case report examples. Depending on the scale of the change being considered and how it is prepare, at that place could be a squad of facilitators, each supporting a number of units or areas. In some cases, a facilitator role may be combined with another part, such as a clinical leader, quality improvement coordinator, knowledge broker or project manager. The specific championship of 'facilitator' is not of import. The crucial thing is that the individuals function as facilitators in that they actively utilize facilitation methods and processes to enable and optimise implementation. In some cases—and particularly where facilitation is office of another part—the facilitator may feel similar a lonely agent. Even so, given the scope and complexity of the role, this is not a desirable situation and can event in individual feelings of isolation and being overwhelmed [62]. Whilst a formal infrastructure might not be, the individuals concerned should exist encouraged to seek opportunities for support and guidance, for case, by establishing a 'buddy' relationship with others in a similar role or identifying a more experienced facilitator to mentor them. Organisations committed to knowledge translation and implementing innovations in healthcare ought to reflect on the infrastructure they have to enable facilitation capabilities and skills to flourish. Otherwise, there is a danger of setting people up to fail without the requisite level of training, skills and support. Table 4 summarises the main descriptors of novice, experienced and expert facilitators.

A final signal in relation to the facilitation construct within i-PARIHS is that in presenting our description of facilitation and outlining the cardinal ingredients within the facilitator's skill repertoire, there may be a suggestion that the process is logical and sequential. The reality, even so, is very different; the interrelationship betwixt the innovation, the recipients and the multiple layers of contexts is often unpredictable, fluid and iterative. Experienced facilitators learn how to manage this uncertainty and keep individuals and teams on track.

(Annotation: Additional file one provides a more than detailed illustration of the facilitator's focus and activities at the level of the innovation, the recipients and the multiple layers of context; Additional file ii outlines a gear up of reflective questions that facilitators tin can employ to call up well-nigh key bug within the different dimensions of implementation.)

The underpinning theoretical antecedents of the i-PARIHS framework

Another criticism of PARIHS was the lack of detail around its theoretical foundations. Unlike other frameworks such as the Knowledge-to-Activeness (K2A) Framework [64] and the Theoretical Domains Framework [65], which identify with a detail theoretical perspective to explain implementation (planned change and behavioural change, respectively), PARIHS claimed an eclectic provenance of relevant theories and philosophical perspectives [1]. In our deliberations with i-PARIHS, we have connected with the theoretical eclecticism but accept tried to present it in a more coherent way [16]. The reason for doing this is twofold: showtime, information technology helps the facilitator to empathise the theoretical antecedents of the problems they are dealing with, and 2d, it helps enquiry and evaluation teams to create a theoretical framework around one or more particular aspects of the implementation process they wish to explore in greater detail. Our identification of relevant theories is necessarily selective; still, nosotros have sought to identify those theories that reflect the core constructs of innovation, recipients, context and facilitation and that are consistent with our overarching view of implementation equally iterative, negotiated and relational. Thus, if a facilitator or a research team studying implementation was interested in understanding what aspects of the bear witness influenced its uptake and use, the i-PARIHS framework would point them in the direction of theories around experiential learning [66], situated learning [67], evidence-based practice [68] and innovation [34, 36, 69]. This would provide insights into the means by which knowledge is acquired, interpreted and applied in a way that is consistent with the i-PARIHS framework; in plough, it would too provide a theoretical perspective that could inform or explicate the innovation and its touch on.

For a facilitator thinking about how to work with individuals and groups, the i-PARIHS framework again points them towards a number of different theories. These include theories of innovation, reflecting the inter-connection between an innovation and the people who have to use it. For example, Rogers highlighted the importance of understanding different groups within the intended audience for innovation and how they are likely to react, every bit well as making employ of peer-to-peer conversations and apparent, trusted teachers and leaders to bring people on board with the change [33, 34]. Problems relating to adopter characteristics are also reflected in the Theoretical Domains Framework [65, lxx] where motivation is considered aslope factors such as role and identity, goals, behavioural regulation, beliefs and capabilities and consequences. Weiner'due south theory of organisational readiness to change [71] proposes that readiness depends on collective behaviour change linked to two primal factors, described as change commitment (wanting to change) and change efficacy (able to change). Insights into these types of theories assist to inform the way that facilitators construction their interventions to achieve the behavioural alter that is required for successful implementation. Equally, they provide research and evaluation teams with a gear up of parameters to frame studies of implementing prove-based innovation in exercise.

Theories that inform our views most the context of implementation are rich and varied, particularly focusing on issues of organisational complication and how organisations learn and utilise new knowledge. Again this is consistent with the multi-dimensional perspective of implementation that the i-PARIHS framework adopts and embedded behavior nigh reflective and responsive learning. Included in this mix are theories related to complexity [72, 73], absorptive capacity [74] and learning organisations [75] as well equally theories related to leadership and organisational culture [76]. Other theories relate to how innovation and change tin be sustained in a system. Once again, there are a number of theories that attempt to explicate this miracle. One that has been practical in healthcare is normalisation process theory [77, 78], which acknowledges the interaction of actors (recipients) within their context and proposes 4 constructs titled coherence, cognitive participation, collective activeness and reflexive monitoring every bit the generative mechanisms required to routinely embed innovations. A further set of theories relevant to the study of context are economic and political theories that govern the external environment, including theories of regulation, marketplace economy, financial incentives and contracting [79].

From this brief overview of theories, a number of mutual themes are apparent which reinforce the complex, dynamic and non-linear nature of implementation and emphasise the importance of experiential learning at the level of individuals, teams and organisations. What is also apparent is the relationship between aspects of the innovation, the recipients and the context. Table five summarises the primal themes that sally from theories relating to the 'what', 'who' and 'where' of implementation and resultant implications for the 'how' issues of implementation.

The final groups of theories informing the i-PARIHS framework are those that inform our views about facilitation. As Tabular array five illustrates, the themes identified from our theoretical analysis have important implications for 'how' the process of implementation is approached. Our position is that the concept of facilitation, with its emphasis on enabling others to human activity, is an ideal way in which to embrace processes that recognise and accommodate to the dynamic and state of affairs-specific nature of implementation, with an emphasis on edifice relationships, learning and flexibility. Every bit others take noted, at that place is still more work to practise on clarifying the concept of facilitation [lxxx, 81]. The theories that take specially influenced our approach to facilitation include those of humanist authors such equally Carl Rogers [82] and John Heron [83]. Fundamentally, this theoretical perspective on facilitation emphasises the importance of enabling others, equally opposed to telling, teaching, persuading or coercing them to act. Nosotros also depict on improvement theories that promote local engagement and buying of the procedure of implementing improvement, peculiarly in thinking virtually how facilitators enact their function in practice. Most notable amidst these improvement theories is Deming's system of profound cognition for improvement, with its focus on understanding systems, processes, experiential learning and homo interaction [84].

Where next?

Our analysis of a range of theoretical, empirical and experiential bear witness gives the states initial confidence in the revisions proposed in the i-PARIHS framework. Yet, just every bit PARIHS has evolved over time, so too we recognise the need for ongoing development and evaluation of i-PARIHS. Our aim in presenting the framework at this signal is to open up up farther discussion and argue. Some specific issues that we would suggest merit farther consideration include the re-conceptualisation of the cadre constructs. From the discussion in the paper, we have tried to delineate the boundaries between the constructs of innovation, recipients and context; yet we know that, depending on the state of affairs, there may be overlap betwixt them thus any attempt to distinguish them may exist imperfect and open for debate. From a pragmatic perspective, we accept attempted to reverberate the inter-connection of the constructs in the spiral representation of i-PARIHS yet at the same time provide practical guidance to those involved in implementation. Whether this is a helpful distinction volition depend on feedback from future users of the framework. Likewise, nosotros recognise that the labelling of the construct 'recipients' may nowadays a rather passive role for the actors involved in implementation. A more active descriptor may be appropriate, particularly to reverberate the role of stakeholders—and most chiefly patients and clients—in shaping the innovation and implementation process.

We have addressed some of the challenges set out in the 2008 newspaper in Implementation Science, notably the need for more theoretical work on PARIHS and more detail on how to operationalise the framework [1]. Clearly, future work is required to examination and refine the proposed i-PARIHS framework as both a diagnostic and evaluative tool within implementation practice and implementation enquiry, particularly through prospective implementation studies. Within such studies, it will be of import to prefer research and evaluation designs that allow in-depth investigation of the core constructs. The inter-play between constructs that influence implementation is generally poorly understood, non least due to the problems of boundary delineation mentioned in a higher place; as such, there is a need for more in-depth longitudinal studies which examine the dynamics of the innovation, the actors involved, the context and the proposed model of facilitation. This in turn, volition inform the ongoing development and refinement of instruments to be used in conjunction with i-PARIHS and its cadre constructs. In parallel, ongoing work to map, use and evaluate the theoretical antecedents of the framework is warranted, specially to further analyze and and so evaluate the effectiveness of facilitators and facilitation as an intervention for knowledge translation.

Conclusions

The PARIHS conceptual framework was developed in an endeavor to stand for the dynamic and multi-faceted nature of implementation in healthcare. The framework has been widely applied, tested, reviewed and refined. Drawing on testify from our own and others' experiences of applying and evaluating PARIHS, this paper presents a revised version of the framework, described equally the integrated-PARIHS or i-PARIHS framework. This reflects the work that has been undertaken to explicitly integrate the conceptual framework with supporting theories and an operational model of facilitation. The revised i-PARIHS framework positions facilitation as the active ingredient of implementation, assessing and aligning the innovation to exist implemented with the intended recipients in their local, organisational and wider system context. Facilitation is operationalised through a network of novice, experienced and expert facilitators applying a range of enabling skills and improvement strategies to structure the implementation procedure, engage and manage relationships between key stakeholders and place and negotiate barriers to implementation within the contextual setting. Nosotros are presenting the revised framework for consideration and debate within the wider implementation science customs, recognising that future work is needed to test its utility, applicability and content and construct validity.

References

-

Kitson A, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARIHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci. 2008;3:ane.

-

Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based do: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Intendance. 1998;7:149–59.

-

Rycroft-Malone J, Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A, et al. Ingredients for change: revisiting a conceptual framework. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;xi:174–80.

-

McCormack B, Kitson A, Harvey Yard, Rycroft-Malone J, Titchen A, Seers K. Getting evidence into practice: the meaning of 'context'. J Adv Nurs. 2002;38(1):94–104.

-

Harvey G, Loftus-Hills A, Rycroft-Malone J, Titchen A, Kitson A, McCormack B, et al. Getting evidence into exercise: the role and role of facilitation. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37(6):577–88.

-

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers M, Titchen A, Harvey G, Kitson A, McCormack B. What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? J Adv Nurs. 2004;47:81–90.

-

Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, Seers K, Kitson A, McCormack B, Titchen A. An exploration of the factors that influence the implementation of bear witness into practice. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:913–24.

-

Estabrooks C, Squires J, Cummings K, Birdsell J, Norton P. Development and assessment of the Alberta Context Tool. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;nine(i):234.

-

McCormack B, McCarthy 1000, Wright J, Coffey A. Development and Testing of the Context Assessment Index (CAI). Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2009;6(1):27–35. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00130.x.

-

Helfrich C, Li Y, Sharp N, Sales A. Organizational readiness to change cess (ORCA): development of an musical instrument based on the Promoting Activity on Research in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2009;4:38. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-iv-38.

-

Seers K, Cox G, Crichton N, Edwards R, Eldh A, Estabrooks C, et al. FIRE (facilitating implementation of research evidence): a study protocol. Implement Sci. 2012;7(i):25.

-

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers Thousand, Chandler J, Hawkes C, Crichton Northward, Allen C, et al. The role of evidence, context, and facilitation in an implementation trial: implications for the development of the PARIHS framework. Implement Sci. 2013;eight(one):28.

-

Kitson A, Marcionni D, Folio T, Wiechula R, Zeitz K, Silverston H. Using cognition translation to transform the fundamentals of intendance: the older person and improving care project. In: Lyons RF, editor. Using evidence: advances and debates in bridging wellness research and activity. Halifax, Canada: Atlantic Health Promotion Research Centre, Dalhousie University; 2010. p. 61–71.

-

Helfrich C, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Daggett G, Sahay A, Ritchie One thousand, et al. A critical synthesis of literature on the promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci. 2010;5:82.

-

Stetler C, Damschroder Fifty, Helfrich C, Hagedorn H. A Guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):99.

-

Harvey Thou, Kitson A. PARIHS re-visited: introducing i-PARIHS. In: Harvey G, Kitson A, editors. Implementing evidence-based practise in wellness intendance: a facilitation guide. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2015. p. 25–46.

-

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers Thousand, Crichton N, Chandler J, Hawkes C, Allen C, et al. A pragmatic cluster randomised trial evaluating three implementation interventions. Implement Sci. 2012;7(i):eighty.

-

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging inquiry and practice. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):337–50.

-

Flottorp S, Oxman A, Krause J, Musila Due north, Wensing M, Godycki-Cwirko One thousand, et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional person practise. Implement Sci. 2013;eight(1):35.

-

Harvey Chiliad, Fitzgerald Fifty, Fielden S, McBride A, Waterman H, Bamford D, et al. The NIHR collaboration for leadership in applied wellness research and intendance (CLAHRC) for Greater Manchester: combining empirical, theoretical and experiential evidence to design and evaluate a large-scale implementation strategy. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):96.

-

Harvey Chiliad, Oliver G, Humphreys J, Rothwell K, Hegarty J. Improving the identification and management of chronic kidney illness in primary care: lessons from a staged improvement collaborative. Int J Qual Wellness Intendance. 2015;27(one):ten–half dozen.

-

Kitson A, Wiechula R, Zeitz K, Marcionni D, Page T, Silverston H. Improving older peoples' care in one astute hospital setting: a realist evaluation of a KT intervention. Adelaide: University of Adelaide; 2011.

-

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts N. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(2):107–12.

-

Estabrooks CA, Thompson DS, Lovely JJ, Hofmeyer A. A guide to knowledge translation theory. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(i):25–36.

-

Rycroft-Malone J. Theory and knowledge translation: setting some coordinates. Nurs Res. 2007;56(4):S78–85.

-

McCormack B, Manley K, Titchen A. Practice development in nursing and healthcare. Chichester, Britain: John Wiley & Sons; 2013.

-

Kitson A, Ahmed LB, Harvey G, Seers K, Thompson DR. From research to do: i organizational model for promoting research-based practice. J Adv Nurs. 1996;23(3):430–40.

-

McCormack B, Manley K, Kitson A, Titchen A, Harvey G. Towards practice development: a vision in reality or a reality without vision? J Nurs Manag. 1999;7(5):255–64.

-

Gibb H. An environmental browse of an aged intendance workplace using the PARiHS model: assessing preparedness for change. J Nurs Manag. 2013;21(2):293–303.

-

Hargreaves D. Creative professionalism: the role of teachers in the noesis society. London: Demos; 1998.

-

Humphreys J, Harvey G, Coleiro M, Butler B, Barclay A, Gwozdziewicz Thousand, et al. A collaborative projection to improve identification and management of patients with chronic kidney disease in a principal care setting in Greater Manchester. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(eight):700–eight.

-

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic kidney affliction: national clinical guideline for early identification and direction in adults in primary and secondary care. London: National Found for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008.

-

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 4th ed. New York: The Gratis Press; 1995.

-

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Printing; 2003.

-

Greenhalgh T, Robert M, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Improvidence of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(iv):581–629.

-

Van de Ven AH, Pollet D, Garud R, Venkataraman South. The innovation journeying. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999.

-

Flodgren One thousand, Parmelli Due east, Doumit One thousand, Gattellari Thousand, O'Brien MA, Grimshaw J et al. Local stance leaders: furnishings on professional person practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Aug 10;(8):CD000125.

-

Kislov R, Harvey 1000, Walshe K. Collaborations for leadership in applied health enquiry and care: lessons from the theory of communities of exercise. Implement Sci. 2011;six:64.

-

Gabbay J, May A. Evidence based guidelines or collectively synthetic "mindlines?" Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary intendance. BMJ. 2004;329:1013.

-

Wieringa S, Greenhalgh T. ten years of mindlines: a systematic review and commentary. Implement Sci. 2015;10:45.

-

Blakeman T, Protheroe J, Chew-Graham C, Rogers A, Kennedy A. Agreement the direction of early-stage chronic kidney disease in primary care: a qualitative study. J Roy Coll Gen Pract. 2012;62:e233–42.

-

Harvey G, Kitson A. A facilitation project to better the direction of continence in European nursing homes. In: Harvey K, Kitson A, editors. Implementing evidence-based practice in healthcare: a facilitation guide. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2015. p. 134–l.

-

Harvey G, Kitson A. Translating testify into healthcare policy and practice: single versus multi-faceted implementation strategies—is at that place a elementary reply to a complex question? Int J Wellness Policy Manag. 2015;4(3):123–half dozen.

-

Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith R, Kirsh S, Alexander J, Lowery J. Fostering implementation of health services inquiry findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

-

Harvey G, Kitson A, Munn Z. Promoting continence in nursing homes in four European countries: the use of PACES as a mechanism for improving the uptake of prove-based recommendations. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2012;10(4):388–96.

-

Wiechula R, Shanks A, Schultz T, Whitaker N, Kitson A. Case report of the PROWL project - a whole-arrangement implementation projection involving nursing and dietetic atomic number 82 facilitators. In: Harvey Yard, Kitson A, editors. Implementing evidence-based practice in healthcare: a facilitation guide. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2015. p. 169–84.

-

Fullard E, Fowler G, Gray M. Facilitating prevention in primary intendance. BMJ. 2004;289:1585–7.

-

Engels Y, van den Hombergh P, Mokkink H, van den Hoogen H, van den Bosch Westward, Grol R. The furnishings of a squad-based continuous quality comeback intervention on the management of primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Brit J Gen Pract. 2006;6:781–7.

-

Liddy C, Laferriere D, Baskerville B, Dahrouge S, Knox L, Hogg West. An overview of practice facilitation programs in Canada: current perspectives and future directions. Healthc Policy. 2013;8:58–67.

-

Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, Miller WL, Palmer RF, Stange KC, Jaen CR. Event of facilitation on practice outcomes in the National Demonstration Project model of the patient-centered medical habitation. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8 Suppl one:S33–44.

-

Parchman M, Noel P, Culler S, Lanham H, Leykum 50, Romero R, Palmer R. A randomized trial of exercise facilitation to improve the commitment of chronic illness care in chief intendance: initial and sustained effects. Implement Sci. 2013;viii:93.

-

Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise facilitation within main care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:63–74.

-

Royal College of Nursing. Quality patient care: the dynamic standard setting system. Scutari: Harrow; 1990.

-

Morrell C, Harvey G. The clinical inspect handbook: improving the quality of health care. London: Baillière Tindall; 1999.

-

Wallin L, Målqvist M, Nga NT, Eriksson Fifty, Persson L-A, Hoa DP, Huy TQ, Duc DM, Ewald U. Implementing knowledge into practice for improved neonatal survival; a cluster-randomised, customs-based trial in Quang Ninh province, Vietnam. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(i):i–9.

-

Persson LA, Nga NT, Malqvist M, Thi Phuong Hoa D, Eriksson L, Wallin L, et al. Effect of facilitation of local maternal-and-newborn stakeholder groups on neonatal bloodshed: cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001445.

-

Stetler C, Legro M, Rycroft-Malone J, et al. Function of "external facilitation" in implementation of research findings: a qualitative evaluation of facilitation experiences in the Veterans Health Assistants. Implement Sci. 2006;1:23.

-

Bidassie B, Williams LS, Woodward-Hagg H, Matthias MS, Damush TM. Key components of external facilitation in an acute stroke quality improvement collaborative in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2015;10:69.

-

Eriksson L, Huy TQ, Duc DM, Selling KE, Hoa DP, Thuy NT, Nga NT, Persson L-A, Wallin Fifty. Process evaluation of a knowledge translation intervention using facilitation of local stakeholder groups to ameliorate neonatal survival in the Quang Ninh province, Vietnam. Trials. 2016;17(1):1–12.

-

Ritchie MJ, Kirchner JE, Parker LE, Curran GM, Fortney JC, Pitcock JA, Bonner LM, Kilbourne AM. Evaluation of an implementation facilitation strategy for settings that experience significant implementation barriers. Implement Sci. 2015;x Suppl 1:A46.

-

Wiechula R, Kitson A, Marcoionni D, Page T, Zeitz K, Silverston H. Improving the fundamentals of care for older people in the acute hospital setting: facilitating practice comeback using a Knowledge Translation Toolkit. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2009;7(4):283–95.

-

Kitson A, Harvey One thousand. Getting started with facilitation: the facilitator's role. In: Harvey G, Kitson A, editors. Implementing prove-based do in healthcare: a facilitation guide. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2015. p. 70–84.

-

Kitson A, Harvey Chiliad. Facilitating an bear witness-based innovation into practice: the novice facilitator'due south function. In: Harvey G, Kitson A, editors. Implementing testify-based practice in healthcare: a facilitation guide. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2015. p. 85–104.

-

Graham I, Tetroe JM. The Cognition to Action Framework. In: Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T, editors. Models and frameworks for implementing evidence-based practice: linking bear witness to action. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. p. 207–22.

-

Pikestaff J, O'Connor D, Michie Due south. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for utilise in behaviour alter and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;seven(1):37.

-

Kolb D. Experiential learning: feel equally the source of learning and evolution. Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ; 1984.

-

Lave J, Wenger Due east. Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Printing; 1991.

-

Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Bear witness based medicine: a move in crisis? BMJ. 2014;348:g3725.

-

Van de Ven AH. Engaged scholarship: a guide to organizational and social research. Oxford: Oxford University Printing; 2007.

-

Michie South, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing prove based practice: a consensus arroyo. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33.

-

Weiner B. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):67.

-

Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ. 2001;323:625–8.

-

Downe S. Beyond evidence-based medicine: complication and stories of maternity care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(1):232–seven.

-

Harvey 1000, Jas P, Walshe One thousand. Analysing organisational context: case studies on the contribution of absorptive chapters theory to understanding inter-organisational variation in performance comeback. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(1):48–55.

-

Senge PM. The fifth bailiwick: the art and practise of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday; 1990.

-

Schein EH. Organizational culture and leadership. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2004.

-

May C, Finch T. Implementation, embedding, and integration: an outline of Normalization Process Theory. Folklore. 2009;43(3):535–54.

-

May C, Mair F, Finch T, MacFarlane A, Dowrick C, Treweek S, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: normalization Process Theory. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):29.

-

Grol R, Bosch Chiliad, Hulscher Thousand, Eccles Thousand, Wensing K. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: the apply of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007;85(one):93–138.

-

Dogherty EJ, Harrison MB, Graham ID. Facilitation as a office and process in achieving evidence-based practice in nursing: a focused review of concept and meaning. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2010;7(2):76–89.

-

Berta Westward, Cranley L, Dearing JW, Dogherty EJ, Squires JE, Estabrooks CA. Why (we remember) facilitation works: insights from organizational learning theory. Implement Sci. 2015;10(one):ane–xiii.

-

Rogers CR. Freedom to larn—a view of What Educational activity Might Become. Charles Merrill: Columbus, Ohio; 1969.

-

Heron J. The facilitator's handbook. London: Kogan Page; 1989.

-

Deming WE. Out of the crisis. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Printing; 2000.

-

Final study summary—Fire (facilitating implementation of research show). Bachelor at: http://cordis.europa.eu/result/rcn/149765_en.html [accessed 15.2.16]

-

Schultz T, Kitson A, Soenen S, et al. Does a multidisciplinary nutritional intervention prevent nutritional pass up in hospital patients? A stepped wedge randomised cluster trial. e-SPEN J. 2014;9(2):e84–90.

-

Wenger E. Communities of do: learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

-

Gabbay J, le May A, Jefferson H, Webb D, Lovelock R, Powell J, et al. A case written report of knowledge direction in multiagency consumer-informed 'communities of do': implications for evidence-based policy development in health and social services. Wellness. 2003;7(three):283–310.

-

Carlile PR. Transferring, translating, and transforming: an integrative framework for managing noesis across boundaries. Organ Sci. 2004;15(5):555–68.

-

Argyris C, Schon DA. Organizational learning 2: theory, method and practice. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley; 1996.

-

McKee L, Charles K, Dixon-Woods K, Willars J, Martin One thousand. 'New' and distributed leadership in quality and safety in health care, or 'onetime' and hierarchical? An interview report with strategic stakeholders. J Wellness Serv Res Po. 2013;xviii(two Suppl):eleven–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Respective author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GH and AK contributed equally to the evolution, writing and terminal approval of the manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Detailed illustration of the facilitator'southward focus and activity at the level of the innovation, the recipients and the inner and outer context. This figure provides further data on specific issues the facilitator may need to consider when planning for implementation. (PPTX 276 kb)

Additional file two:

Reflective questions that facilitators tin utilise to think about fundamental issues inside the different dimensions of implementation. This file presents a tool for cocky-assessment that facilitators can use to consider their own strengths and areas for evolution in supporting implementation. (PDF 205 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you requite appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/goose egg/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated bachelor in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Virtually this commodity

Cite this article

Harvey, G., Kitson, A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of cognition into practice. Implementation Sci eleven, 33 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2

-

Received:

-

Revised:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2

Keywords

- PARIHS

- i-PARIHS

- Implementation framework

- Facilitator role

- Facilitation

What Is Promoting Action On Research Implementation In Health Services (Parihs) Framework,

Source: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2

Posted by: arnoldforthemight.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is Promoting Action On Research Implementation In Health Services (Parihs) Framework"

Post a Comment